Approximation Algorithm Comparison

Contributors

[1] Li, Ryan Jun-Man (Email: rli342@gatech.edu)

[2] Morioka, Hatsune (Email: hmorioka3@gatech.edu)

[3] Shin, Bomm (Email: bshin8@gatech.edu)

[4] Wang, Gabriel Qi (Email: gwang340@gatech.edu)

Note that the following is a simplified report with sections edited for simplicity. For a more in depth and comprehensive report, there is a PDF included within the repository.

Introduction

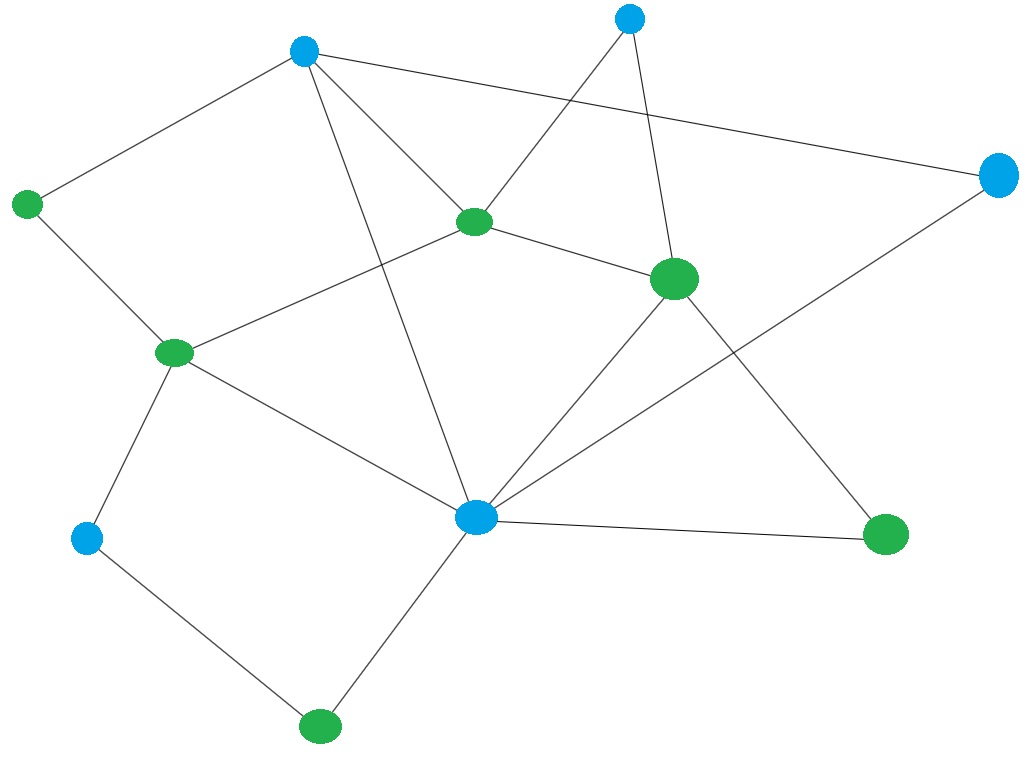

In this paper, we discuss and implement different algorithms for building a Minimum Vertex Cover (MVC) to evaluate the accuracy and speed of each implementation. The MVC problem is defined by finding the minimum size set of vertices so that for all the edges in the graph at least one vertex per edge is within the output set of vertices. The implementations we chose were Branch and Bound, Approximation, Genetic Algorithms, and Stochastic Local Search. For the Approximation algorithm, it found a vertex cover in a short amount of time, but the effect was an inaccuracy of up to 2 times the amount of vertices chosen as the optimal solution. For the Branch and Bound algorithm, we formulated a binary state-space tree to search for an exact solution with upperbound and lowerbound for pruning purposes. While accuracy is guaranteed, the running time is exponential to the input size. Hence, a time limit of 600 seconds were imposed on the algorithm to run on each input. For the Stochastic Local Search, it found a relatively accurate result, however, it takes a large amount of time until it reaches to the local minima for dense graphs. Setting a cut-off time to reduce running time can lead to a considerable drop in accuracy in this algorithm, so it is hard to predict a reasonable cut-off time. Finally, Genetic Algorithms found relatively accurate results for smaller graphs, but tended to get caught in local minimas for larger graphs once a valid vertex cover was found. While it could probably find better solutions, it would take an infeasible amount of time.

Related Studies

The Vertex Cover Problem is an NP-Complete graph problem which is similar to problems like the Independent Set Problem and Edge Cover Problem. And the Vertex Cover Problems can be re-formulated as a half-integral linear programs such as the Maximum Matching Problems.

The Vertex Cover Optimization Problem serves as a model for many real-life problems. For example, an establishment that wants to find the fewest possible camera installment covering the hallways (edges) connecting all rooms (nodes) on a building of a floor might be the objective of the Minimum Vertex Cover Problem.

Approximation

To create a MVC using a construction heuristic with approximation guarantees, the approximation algorithm runs through the graph to add vertices based on unused edges. The code has two sets to keep track of: the set of edges and vertices. The edges set is initialized as the entire set of edges in the graph which the vertices is set to an empty set. The code then runs through and randomly selects edges to add both vertices to the vertices set. We used a random seed of 100. Once those two vertices are added, all edges that contained either vertex will be removed from the edges set. Once there is no more edges left, the algorithm ends and returns the set of vertices.

This algorithm is a poly-time 2-approximate algorithm meaning that the returned set of vertices is at most twice the size of the optimal MVC.

The Time and Space Complexity are O(E*E) and O(E + V) respectively.

The strengths of this algorithm is it’s simplicity. The code is small and easy to understand, but this results is a inaccurate output. The clear weakness of this algorithm is that it typically doesn’t provide the optimal solution due to the fact that it adds both vertices when adding a new edge meaning that that edge has been covered twice.

Local Search (Genetic Algorithms)

To create a MVC using genetic algorithms, we have to define a few terms. First, how will an individual in a population be represented? In our case, we define an individual as a subset of vertices from the original graph. By definition, a MVC is a subset of vertices that connects to every edge in the graph. Therefore, we can use this set representation as our individual, and our population will simply be a list of sets, where each set is an individual that can be evaluated. Individuals can be initialized randomly this way very easily as well. We can simply create a random subset of vertices to act as an individual, then add it to the population. Since we now have an individual and population, next we need to define how we are evaluating the individuals.

We can use the cost function defined in the description, where Cost(G, C') = number of edges not covered by C'. We want to minimize the number of edges not covered by C', as a valid vertex cover would have a cost of 0 as it covers every edge. However, we also want to minimize the number of vertices in the cover, as the definition of an MVC is the vertex cover with the minimum number of vertices possible. Therefore, we can use multi-objective optimization here. We want to minimize both our Cost, as defined above, and minimize N, the number of vertices in the individual. We can consider our total “fitness” function as the simple sum of those two objectives. Fitness(G, C') = Cost(G, C') + N. However, we always want to produce a valid vertex cover, so we want to encourage solutions that are valid. Invalid solutions will always have a Cost(G, C') > 0, therefore if Cost(G, C') > 0 we add a high constant to its fitness to encourage finding more valid individuals.

Next we must define how we will actually search for the optimal solution. As we mentioned, we randomly initialize individuals by creating random subsets. We have implemented two ways to help the population search the space and find the best solution.

Method 1: Mating

We have implemented something similar to traditional crossover methods. In traditional genetic programming, individuals are represented as trees and we exchange subtrees between individuals. In our case, since our individuals are sets, we look for the difference between the two sets. Given the individuals A and B, we can form two lists of the differences between the sets. Let us create 2 lists, L_{1} and L_{2}. L_{1} contains all the nodes in A but not B and L_{2} contains all the nodes in B but not A. Given these two lists, we randomly select half of the nodes, and exchange them between the individuals. This way, each individual produces a new “child” with a new set of vertices for the next generation.

Method 2: Mutation

Since our individuals are sets, we can randomly add, remove, or replace a node in a set to act as a mutation. For remove, we randomly remove a vertex from the set. For add, we add a random possible vertex from the set of all possible vertices. Finally, if we replace a node, we randomly remove a vertex from the set then add a random vertex from the possible vertices. So mutating an individual will change the solution in some way which we can then evaluate.

Finally, we discuss how we select individuals for the next generation. We can evaluate individuals using our two objectives stated above. So in order to select individuals for the next generation, we use a simple tournament selection method where we randomly split the population into groups of 3, then of those groups of 3, we select the individual with the best combined fitness from our objective functions. The selected individuals are then used for the next generation. We also introduce the idea of elitism and pareto dominant individuals. Unlike other search algorithms, genetic algorithms keeps a population of possible solutions, therefore we can store and persist good individuals for multiple generations. We keep the best individuals from each generation, and select them to continue to the next generation. This is the concept of elitism. However, since we have multiple objectives that we are trying to minimize, there is not a single “best” individual per generation. But rather, multiple solutions that perform better at a certain objective compared to other individuals. This produces the concept of pareto dominant individuals, where we can create a boundary between individuals who have “optimal” fitness for objectives combinations and individuals who cannot perform better than the boundary individuals at any objective. So combining the concepts of elitism and pareto dominance, at each generation, we select the pareto dominant individuals and allow them to continue to the next generation.

Plots

In order to plot QRTDs, SQDs, and Box plots, we used ten different results obtained with random seed = 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100 for each of power.graph and star2.graph. Unfortunately, most of the solutions found by genetic algorithms for larger graphs were very large vertex covers. Since the quality of the solutions produced were very poor, our plots reflect that. Unfortunately, since our solutions did not reach the minimum thresholds for quality, there were 0 quality solutions that met our criteria. Because of this, our QRTDs and SQDs are horizontal lines at 0. If the genetic algorithm was given more time, it likely would have found a solution that met our minimum thresholds. We could have also changed our q* value to better reflect our results, however, we aren’t sure what would be a reasonable q* in this scenario. Look at our Stochastic Local Search section for more plots that better represents a scenario with good solutions that are found.

Local Search (Stochastic Local Search)

Algorithm Description

Stochastic local search is an algorithm which uses a randomized initial state and randomized steps in a searching process. In our algorithm, we used a whole set of nodes V of a given graph G = (V, E) instead of a random sample of nodes as an initial state. In addition, we used an enhanced way of randomized selection to choose the next state to test rather than a completely randomized selection to make a more efficient selection at each step.

First of all, our initial state is a whole set of nodes V of a given graph G = (V, E). A set of all nodes in a graph is guaranteed to be a vertex cover, so it is a good candidate solution to start with. Let C denote this candidate solution.

Second of all, we search through each node in G one by one in order of increasing number of its neighbors (degree) to determine whether it should be included in a vertex cover or not. Clearly, a node of higher degree is more likely to be in a vertex cover because it covers more edges, so it is safer to remove a node of lower degree from our candidate solution C. Taking this into account, we can achieve a more efficient method of a randomized selection of a next candidate solution to test as follows:

Sort a set of nodes V in a graph G in order of increasing degree. Let Q denote this sorted list of nodes.

Pick up a node i from Q to test whether it should be included in a vertex cover in order of increasing degree. If we decide not to include i in C, then remove i from C. If there are more than one node of the same degree, then pick up a node randomly from the set of nodes of the same degree. We test each node only once, so we will not test the same node multiple times.

This algorithm helps us avoid searching through a huge number of candidate solutions to find a next move because it uses a sorted list Q to pick up a next candidate solution which is most likely to improve a current solution. It narrows down the searching space at each step. In addition, this algorithm prevents a solution from hitting local minima by using a sort of randomized selection of a next state. However, it is time-consuming to remove a picked-up node from the sorted list Q at each step inside a while-loop because we implemented Q using a list data structure in python.

Time and Space Complexities

Our Stochastic Local Search implementation has three major processes:

Sorting V of G = (V, E) in order of increasing degree

Counting the number of edges in G = (V, E) not covered by a candidate solution C

Actual local searching process

Time Complexity:

Firstly, sorting takes O(n log n). A graph G = (V, E) is represented as a dictionary in our implementation, where the key is a set of all nodes V and the value is a set of neighbors corresponding to each key node. Thus, sorting V of G = (V, E) in order of increasing degree is equivalent to sorting keys of a dictionary by the size of corresponding sets. Secondly, counting the number of edges in G = (V, E) not covered by a candidate solution C takes O(|V| *|E|). Finally, our actual local search steps take O(|V|^2 * |E|) because we search through each of nodes V of G = (V, E), and for each of those, check the number of edges in G = (V, E) not covered by a candidate solution C.

Space Complexity:

Space complexity of this algorithm is O(|V|), which is the size of the set of nodes Q, sorted in order of increasing degree.

Empirical Evaluation

Branch and Bound Algorithm

This data was performed using Intel Core i5 Processor, 8GB RAM and Python 3. The Branch and Bound Algorithm was expected to take longest time out of other algorithms. However, the search space started with a maximum degree node, the most “promising” node, the total time of traversal is reduced. The results shown in Table 3 were all found within 600 second time cut-off.

Approximation Algorithms

This data was performed using an Intel Core i7 processor, 8GB of RAM, and Python 3.

Local Search (Stochastic Local Search)

This data was performed using an Intel Core i5 processor, 8GB of RAM, and Python 3. RandomSeed = 100 was used for all the graphs.

Local Search (Genetic Algorithms)

This data was performed using an Intel Core i5 processor, 8GB of RAM, and Python 3. RandomSeed = 100 was used for all the graphs. Genetic Algorithms tends to have a longer run time, as it depends on the size of the initial population and the time required to evaluate all those individuals. It also tends to find solutions slower due to crossover and mutation, however, it does tend to find some novel solutions that other methods don’t.

Discussion

Approximation Algorithm

The Approximation Algorithm seemed to follow in line with our expectations of the time complexity besides the MVC for “Star2”. “Star2” had the largest amount of edges, but completed faster than “Star”. This difference could have been correlated to a significant amount of edges being removed early in “Star2” relative to “Star”. However, besides this set, the rest of the graphs seemed to be aligned with the notion that the time complexity is O(E*E).

When it came our expectation of the evaluation criteria, the approximation algorithm did follow the poly-time 2-approximation as no output had a MVC of over 2 times the optimal. Each algorithm finished in a relatively quick time span.

Genetic Algorithms

The Genetic Algorithm approach results are in line with our expectations for relative error for smaller graphs, however for larger graphs such as “Star2” and “Power” it performed very poorly. This may be due to how genetic algorithms tend to maintain and exploit existing valid solutions using our elite pool and prevents too much negative change. For example, a valid vertex cover could contain every possible node in the graph. However, it obviously is far from the Minimum vertex cover. But, since it is a valid solution, the genetic algorithm fitness function would rate it higher than an invalid solution. Because of this, when large individuals are initialized in the first generation, they are more favored as they are more likely to be valid. It then takes a very long time for the large individuals to start shrinking down to approach the true minimum vertex cover. This may be why genetic algorithms are performing poorly on these larger graphs. Another hypothesis could be that the initial population size is too small, and because of this, individuals are too similar in later generations, causing it to get caught in local minima that it cannot escape. Because of the very poor results on larger graphs, the Stochastic Local Search would likely be better. As the run times and the relative quality of the solutions found by genetic algorithms were very poor, the QRTD and SQD plots for genetic algorithms were horizontal lines at 0, as the necessary relative quality would be extremely high in order to show the solutions, so in most cases, none of the solutions produced by genetic algorithms had met the quality threshold because none of them had good relative error for larger graphs.

Stochastic Local Search

Our implementation of Stochastic Local Search randomly picks up a next state from a set of nodes of the same degree to move to at each step, so the running time varies especially for dense or large graph because it has more choices of states we can move to at each step. The variance of running time is visualized by the box plots. Additionally, the running time of computing the objective function used in our implementation is O(|V| * |E|), so the running time is significantly affected by dense graphs. However, the result we obtained in terms of the accuracy was satisfactory without being stuck in a low-quality local minima.

Conclusion

In general, the choice of algorithm to solve MVC problem should be based on the required accuracy and available computing resources. If there is no limit to computing resources with high accuracy requirement, Branch and Bound algorithm is suitable. However, if quick approximation is required in spite of sacrificing the accuracy, heuristic algorithms such as the Local Search Algorithm or Approximation Algorithm should be used. Genetic Algorithms appear to find promising novel solutions in smaller graphs that other search algorithms don’t find as easily, however, it tends to overexploit the valid solutions it already found and get caught in local minima, causing it to perform poorly on larger graphs. Due to nature of NP-Complete problem, if one can reduce any particular NP-Complete problem into a MVC, any algorithm outlined in this report can be applied.

Approximation Algorithm Comparisons